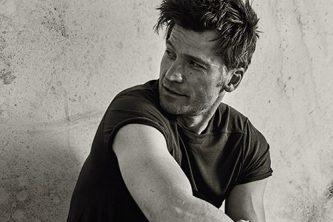

Africa Rising: Designer Teddy Ondo Ella Designs for Graphic Appeal

Image: Etienne Gilfillan.

Returning was a gambit for Teddy Ondo Ella, the self-taught entrepreneur and designer. He recalls boarding a plane bound for Libreville, the Gabonese capital, with office equipment in the hold and 20 dollars in his pocket. All he knew then was that he wanted to open a business in his home country on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa. “Taking risks and making mistakes is not a big deal,” he says. “Even Steve Jobs failed. But there is no excuse for ignorance, especially with the Internet.” Several years down the line, Ondo Ella is still on the upswing of that belief with the launch of his eponymous brand, a foray into the luxury menswear segment inflected with African inspirations and high-end global standards to debut this July in New York. “I’m adamantly against putting people in boxes,” the designer says. “Borders only exist in our minds.”

Video: Only Made in Gabon.

Multicultural from birth, Ondo Ella, 38 this June, was born in Congo, where his Gabonese father worked for an airline and his Congolese mother owned a store named after her son, Teddy Boutique. That is where he caught the entrepreneurial and fashion bugs, he recalls now, learning the ropes of the business and accompanying her on buying trips to Europe. The family moved back to Libreville when he was a child, but he would eventually leave again for school in France. “Sending your children to be educated in the former colonizing power is a way to open them to a wider world,” he explains.

When Ondo Ella returned to Gabon for the second time, it was because he felt he would have more opportunities at home, where he could apply the breadth of his skills, rather than abroad. “France has everything—taste, gastronomy, elegance—but you can quickly get stuck in an everyday tedium.” There, he studied IT management systems, but soon enough left to get a job selling ad space. On the side, he was involved in the hip-hop and rap scenes—he even released an album of his own—traveled extensively, and cultivated his business acumen through various projects.

Image: Teddy Ondo Ella.

Flush with the success of his first enterprise, a marketing agency, Ondo Ella opened Sneakers Club in Libreville, where he offered limited edition kicks and even began selling a few garments. In 2012, he launched a capsule named Only Made In Gabon, which borrowed from street and African cultures. This trial run was an opportunity to observe customer behavior and learn about the garment supply chain. The fashion culture acquired at his mother’s knee continued to mature, and it wasn’t long before he made plans for Teddy Ondo Ella, the collection.“I’m an African designer with an African brand, but for the global fashion market,” he notes. Although the key silhouette of his sartorial line will be the abacos, a tie-less suit that rose to prominence in the ‘70s as a reaction to colonialism, any folkloric notions are far from his mind. He cites Marc Jacobs, Tom Ford, and English-Ghanaian designer Ozwald Boateng as inspirations, the latter specifically for his definition of a new, fitted silhouette, and considers his brand gateway between the continent and the Western world. The appeal has to be graphic, not geographic. “My African identity gives me grounding, but I want it to translate into a contemporary wardrobe that won’t scare off a non-African customer,” he says. “The common denominator is taste. Elegance in one country is elegance everywhere.”

Image: Teddy Ondo Ella.

Still in the developmental stages today, the inaugural Teddy Ondo Ella collection is an homage to Africa’s vivid sartorial culture. “The [Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People] movement is peaceful, with a deep appreciation of craftsmanship and quality, and a set of codes, such as rejection of fascism and racism, that go well beyond garments,” he explains, showing sketches that include his take on the abacos style in neutral shades and geometric motifs, cotton shirts, and accessories. They all are in an appealing palette well-suited for the modern gentleman, subtly influenced by the continent’s identity. “For me, it’s about creating clothes that are aesthetically pleasing, even before you learn of their meaning and history.” A staunch believer in the role of art and culture in the development of the nation, as a vector for lasting modernization, he wants to hold the culture of his homeland aloft. “The brand is just a vehicle,” he says. “It’s not about the clothes, it’s about the Gabonese lifestyle and culture.” For his forthcoming New York debut, the designer has secured an Okoukoué performance, a traditional spiritual dance that is rarely seen outside of the country. Beyond fashion, Ondo Ella has his eyes firmly set on a bigger picture. One goal is to bootstrap his success into a template for designers, artists, and creatives to follow. But he’s no role model. “That implies perfection,” he jokes. “Parents don’t encourage creative careers in Africa. They’d rather have a doctor in the family. I want to show that you can make a good living out of creative pursuits.”

Image: Teddy Ondo Ella.

To that end, he plans on opening stores in Gabon that will showcase local artists alongside his designs, and to invite artists such as Bradley Theodore—they recently met through business connections—for takeovers as early as 2018, to highlight the vivid cultural landscape of Libreville. The timing could not be more impeccable. Not only is the continent’s fashion scene emerging slowly on the global stage, but the Gabonese government is taking steps to turn the country into Africa’s Singapore by 2025. Further down the line, Ondo Ella dreams of parlaying his businesses into Africa’s version of an LVMH, branching out into art, gastronomy, hospitality, and even education. He knows Gabon is a small market, particularly in the luxury sector, and he hopes his enterprising example is contagious for neighboring countries. “Preventing the loss of local talent means giving them a reason to stay by creating jobs rather than distributing aid,” he says. “Infrastructures in the region aren’t ready, but it’s important to prepare for what comes after exploiting natural resources when manufacturing and the tertiary sector are on the rise. If you make it in Gabon, given all the changes, you have the mettle to succeed anywhere.”